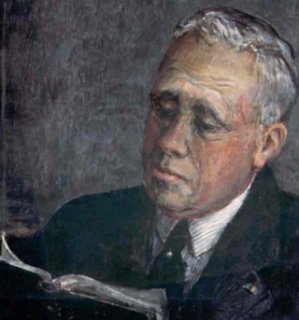

Chesterton on Aquinas

I've been enjoying G.K. Chesterton's biography of Thomas Aquinas in preparation for a class on Calvin and Aquinas. It is not only a biography, but also an introduction to the philosophy of Aquinas. There are an endless amount of quotable passages from this biographical sketch of one of the Church’s greatest theologians by one of it’s greatest defenders of Orthodoxy. Chesterton has a knack for boiling down the essentials truths of very difficult concepts into pithy one liners. Here is a bit of lengthy passage on Aquinas’ understanding (and subsequently, Chesterton’s own understanding) on the role of apologetics:

I've been enjoying G.K. Chesterton's biography of Thomas Aquinas in preparation for a class on Calvin and Aquinas. It is not only a biography, but also an introduction to the philosophy of Aquinas. There are an endless amount of quotable passages from this biographical sketch of one of the Church’s greatest theologians by one of it’s greatest defenders of Orthodoxy. Chesterton has a knack for boiling down the essentials truths of very difficult concepts into pithy one liners. Here is a bit of lengthy passage on Aquinas’ understanding (and subsequently, Chesterton’s own understanding) on the role of apologetics:If there is one sentence that could be carved in marble, as representing the calmest and most enduring rationality of his unique intelligence, it is a sentence which came pouring out with all the rest of this molten lava. If there is one phrase that stands before history as typical of Thomas Aquinas, it is that phrase about his own argument: “It is not based on documents of faith, but on the reasons and statements of the philosophers themselves.” Would that all Orthodox doctors in deliberation were as reasonable as Aquinas in anger! Would that all Christian apologists would remember that maxim; and write it up in large letters on the wall, before they nail any theses there. At the top of his fury, Thomas Aquinas understands, what so many defenders of orthodoxy will not understand. It is no good to tell an atheist that he is an atheist; or to charge a denier of immorality with the infamy of denying it; or to imagine that one can force an opponent to admit he is wrong, by proving that he is wrong on somebody else’s principles, but not on his own. After the great example of St. Thomas, the principle stands, or ought always to have stood established; that we must either not argue with a man at all, or we must argue on his grounds and not ours. We may do other things instead of arguing, according to our views of what actions are morally permissible; but if we argue we must argue “on the reasons and statements of the philosophers themselves.”

I would love a little bit more of an explanation of these “other things” that we may do instead of arguing. My assumption is that Chesterton is talking about a robust declaration of the revealed truth of the Gospel message as distinct from reasoning with people on their own terms through the discipline of philosophy to remove obstacles to belief. If this is the case, than I can think of no better way to express the role of the philosophical endeavor in the life of the Christian.